CASE NOTES

Branhamella ovis and Chlamydia pecorum isolated from a case of conjuctivitis (with some polyarthritis) in lambs

Evelyn Walker, District Veterinarian, Central West LHPA, Dubbo

Posted Flock & Herd April 2013

History

A sheep producer from the Narromine area reported arthritis and conjunctivitis in one mob of 380 three to four month old first cross lambs at foot in mid July 2012. The lactating ewes were minimally affected. The owner had a similar outbreak of severe arthritis and conjunctivitis in November 2011 in weaned lambs. In this case, however, the owner reported that conjunctivitis was the predominate feature with arthritis occurring with less severity compared to last year.

Conjunctivitis was first noticed when the lambs were yarded for their second 5-in-1 vaccination. Only 3% of lambs were affected when symptoms first developed. At the time of the property visit, symptoms of conjunctivitis and mild arthritis had been present for approximately 3 weeks and the infection rate had increased to 5%. While only a small percentage of the lambs showed symptoms, the owner reported that overall the lambs were doing poorly despite good feeding conditions. The lambs and their mothers have been on dryland lucerne (Medicago sativa) the entire time withad lib. grain access to lick feeders. Weaning of these lambs was planned for August/September.

Clinical examination and gross pathology

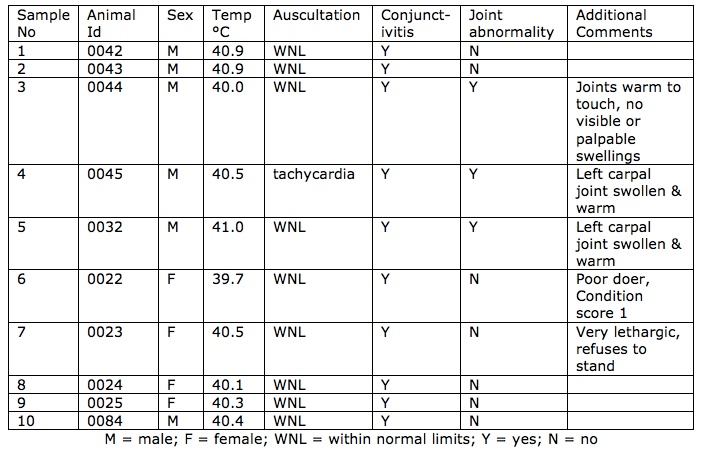

At the time of examination, no affected lambs had died and no lambs were sacrificed for necropsy. Lambs and ewes were examined in the yards. The eye lesions consisted of bilateral conjunctivitis, an ocular discharge ranging from clear to yellow, yellow crusts, and swollen conjunctivial membranes with or without hyperaemia. (Figures 1a & 1b.) There was no evidence of blindness and no foreign bodies were found in the eyes of any of the animals examined. Many of the lambs with eye lesions were also noted to have a concurrent bilateral clear nasal discharge and some had diarrhoea. Some of the affected lambs appeared stiff with palpable joint swellings. (Figure 2). There were no clinical signs suggestive of foot rot or laminitis in the mob. Ten affected lambs were examined. See table 1 below.

Table 1: Clinical findings of affected lambs

Two voided urine samples were collected from two ewe lambs (animal ids 0022 and 0024).

A few adult lactating ewes had bilateral epiphora and resolving ocular discharge. Overall, the adult ewes had no clinical evidence of concurrent conjunctivitis. One ewe was noticeably blind. She had bilateral severe corneal opacity with scarring, conjunctival hyperaemia and oedema. (Figure 3.) There was no ocular discharge. Affected eyes appeared to be in the healing stages. Temperature was normal.

Post-mortem examination was carried out on one adult ewe that died on the way to the yards. Traumatic cervical spinal cord injury was the likely cause. No other abnormalities were seen on post-mortem.

Figures 1a and 1b. These show conjunctival oedema, epiphora, crusting, ocular

discharge and photophobia of affected young lambs

Figure 1b

Figure 2. Affected lamb with swollen carpal joint, nasal discharge and conjunctivitis (not pictured)

Figure 3. Affected adult ewe demonstrating corneal opacity, scarring, conjunctival hyperaemia and oedema

Branhamella ovis (Moraxella ovis), Mycoplasma spp. and Chlamydia spp. were considered as the possible infectious agents in this case. Eleven conjunctival swabs were sent to EMAI for selective bacteriology culture and identification. Twelve conjunctival swabs as well as vaginal and rectal swabs from affected lambs and adult ewes were submitted to Adam Polkinghorne (Queensland University of Technology) for Chlamydia PCR testing and analysis.

Eleven jugular blood samples (10 lambs and 1 adult ewe) were collected in plain vacutainer tubes and submitted for Chlamydia serology and biochemistry. Tests for calcium, magnesium, and lactate were requested to rule out metabolic causes of lameness.

Erysipelothrix, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia were considered the most likely pathogens causing the arthritis. No lambs were available to sacrifice for joint histopathology and bacteriology culture.

Diagnostic test results

Urinalysis was performed in the field on two voided urine samples. They both had pHs of 9 and 8 with the remainder of the urinalysis unremarkable.

Six out of eleven conjunctival swabs were positive for Branhamella ovis. All conjunctival swabs were negative for Mycoplasma. Five out of twelve conjunctival swabs were positive for Chlamydia pecorum. Eight out of 11 blood samples were negative on Chlamydia CFT. Three out of 11 blood samples had titres of 8 and 16 on Chlamydia CFT. All biochemistry findings were within normal range. One out of 6 vaginal and 3 out 12 rectal swabs were positive for Chlamydia pecorum.

Investigation is ongoing to determine if the Chlamydia pecorum strains from the conjunctival, vaginal and rectal collection sites are the same.

Treatment

In previous outbreaks, the owner treated with long-acting injectable oxytetracycline. The owner observed that treated and untreated animals did not differ significantly in their recovery and animals would later relapse despite treatment. No veterinary treatment was administered to the affected animals in this case.

Diagnosis

Based on testing done to date, this case reports conjunctivitis due to Branhamella ovis and Chlamydia pecorum. Chlamydia pecorum strain investigation and typing is ongoing. Potential infectious agents involved in arthritis seen in previous cases as well as this current case have not been fully investigated at this point due to lack of suitable animals to euthanize for joint histopathology and bacteriology.

Follow up

The property was visited approximately one month later. Animals that were previously affected with conjunctivitis had almost completely resolved. However, additional new cases of conjunctivitis, arthritis and upper respiratory signs were now affecting other lamb mobs. Bloods were collected for Chlamydia serology testing of the originally affected animals as well as from new clinical cases. Three out of 13 samples were negative on Chlamydia CFT. Seven out of 13 blood samples had titres of 8 and 16 on Chlamydia CFT. Three out of 13 blood samples had Chlamydia titres ≥16.

All biochemistry findings were within normal range. Conjunctival, nasal, vaginal and rectal swabs from newly affected lambs have been submitted for further testing at Queensland University of Technology. It is planned to report additional findings at a later date.

Discussion

This case is of interest for several reasons. Firstly, two infectious agents were isolated, Branhamella ovis and Chlamydia pecorum. Both can cause conjunctivitis although their relative roles were not determined. Secondly, this case occurred in lambs prior to weaning. In our experience, chlamydial polyarthritis occurs most commonly post weaning. Finally, Chlamydia were isolated from the conjunctiva and also from the rectum and vagina but sero-conversion was limited with only 3 of 11 samples positive at titres of 8 and 16 on initial testing.

Branhamella ovis (B. ovis) has been frequently isolated in both healthy sheep, as part of the normal flora and in sheep with infectious keratoconjunctivitis1,2. In cattle, Moraxella bovis is regarded as the primary cause of infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK),8,9 however, Moraxella (Branhamella) ovis has been isolated from cases of IBK overseas3,6. Others have suggested the B. ovis was opportunistic4,5. Further studies in cattle have indicated that B. ovis produces exotoxins and may therefore contribute to the pathogenesis of IBK6. In this case, B. ovis may be the primary infectious agent but could also be secondary or acting synergistically with C. pecorum in the conjunctivitis in these lambs. Polyarthritis has been described as the most prominent feature of Chlamydial disease in sheep7. The role of Chlamydia pecorum in causing conjunctivitis and arthritis is not yet well understood.

This case demonstrates the challenges associated with making a Chlamydia diagnosis. Chlamydia CFT is the standard method for diagnosing chlamydial infections in livestock given its ease of use and cost-effectiveness. Swabs for routine and selective bacteriology culture and PCR of several animals are costly and time consuming and as result are rarely done. Using the results of Chlamydia CFT alone may not provide an accurate diagnosis. In this case, initial Chlamydia titres were unremarkable with 73% negative and 27% inconclusive. Follow up investigation of the same animals a month later demonstrated 20% negative, 60% inconclusive and 20% positive on Chlamydia CFT. Conjunctival swabs for Chlamydia PCR however demonstrated that 42% were positive. It is of interest that animals that were positive on conjunctival swabs were negative or inconclusive on follow up Chlamydia CFT.

It is possible that this is primarily a case of conjunctivitis with Branhamella the principle pathogen and Chlamydia a secondary agent. This would explain the modest antibody response. The isolation of Chlamydia from multiple sites may in fact suggest a carrier status in some lambs. Other cases (not yet published) seen in the Central West where obvious clinical lameness is present with or without conjunctivitis (and therefore presumably primarily chlamydiosis), antibody titres are strongly positive.

It is also possible that the low titres are because the disease is at its end stages rather than in its acute form. Further investigation into understanding the pathophysiology, epidemiology, and the significance of Chlamydia infections in the sheep industry is required so that better advice on management and treatment of the disease can be provided.

Acknowledgments

This Chlamydia project would not be possible without the ongoing assistance of Warren Skinner, Susan McClure, Adam Polkinghorne, Martina Jelocnik, and EMAI Menangle veterinary laboratory. Thank you.

References

- Dagnall GJR (1994) An investigation of colonization of the conjunctival sac of sheep by bacteria and mycoplasmas Epidemiology and Infection 112:561-567

- Dagnall GJR (1994) The role of Branhamella ovis, Mycoplasma conjunctivae and Chlamydia psittaci in conjunctivitis of sheep British Veterinary Journal 150:65-70

- Maroon G et al. (1968) Ceratoconjunctivite infection ciosa de bovinos provocada por Neisseria Instituto Biologico, Sao Paulo 35:173-179

- Baptista PJHP 1979 Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. A Review. British Veterinary Journal 135:225-242

- Mehle J (1970) Neisseria ovis i keratokonjunktivitis bika Veterinarski Glasnik 24:691-694

- Cerny HE et al. (2006) Effects of Moraxella (Branhamella) ovis culture filtrates on bovine erythrocytes, peripheral mononuclear cells, and corneal epithelial cells Journal of Clinical Microbiology pp 772-776

- Beveridge WIB (1981) Polyarthritis of lambs. Animal Health in Australia Vol 1; Viral Diseases of Farm Livestock. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service

- Parkinson TJ, Vermunt JJ and Malmo J (2010) Diseases of Cattle in Australasia. A comprehensive textbook (New Zealand Veterinary Association Foundation for Continuing Education, Wellington)

- Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW and Constable PD (2007) Veterinary Medicine, 10th Edition